Kosteska v Magistrate Manthey & Anor [2013] QCA 105:

“This is not the first case in which Ms Kosteska‟s argument has been advanced. It, and others like it, have wasted the time of the courts and opposing litigants, together with taxpayers‟ money for some time. This is not a peculiarly Australian problem. Similar fruitless cases have burdened the Canadian courts – so much so that Associate Chief Justice Rooke has examined in detail the characteristics, indicia and concepts of what he describes as “Organised Pseudolegal Commercial Arguments.”

A Frivolous plea is a sham, and considered devoid of any legal merit. It is clearly insufficient on its face, and does not controvert the material points of the opposite pleading. And while it’s allegations may possibly be true, it is totally insufficient in substance as it is irrelevant to the charge.

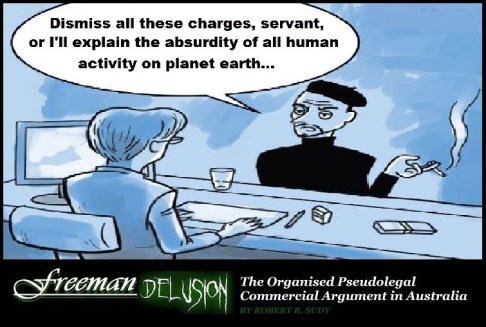

An OPCA argument that denies Court authority cannot succeed due to the courts inherent authority. It is therefore, an intrinsically frivolous and vexatious argument. Insisting on its recognition may well be considered as contempt, the time spent considering it is certainly an abuse of process. It’s sort of like the legal equivalent of an ad hominem response, attacking a person’s character instead of presenting a valid argument.

Butterworths Australian Legal Dictionary, 1997, contains a useful summary of the meaning of the term frivolous and vexatious as follows:

“Frivolous and vexatious Insupportable in law; disclosing no cause of action, groundless: Dey v Victorian Railways Cmrs (1949) 78 CLR 62 at 91. The phrase is generally used with respect to a statement of claim intended to commence legal proceedings. A court may refuse to allow an action to proceed if it considers the actions to be frivolous and vexatious: (CTH) High Court Rules O 26 r 18; (CTH) Federal Court Rules O 21 r 1; (NSW) Supreme Court Rules Pt 13 r 5. An action may be deemed frivolous and vexatious if it is ‘so obviously untenable that it cannot possibly succeed’, or is ‘manifestly groundless’, or ‘so manifestly faulty that it does not admit of argument’. Similarly, a court may refuse to hear an action where ‘under no possibility can there be a good cause of action’, or it is ‘manifest’ that to allow the pleadings to stand would ‘involve useless expense’: L Grollo Darwin Management Pty Ltd v Victor Plaster Products Pty Ltd (1978) 19 ALR 621; 33 FLR 170.”

An OPCA defendant will genuinely believe that what they are submitting has legal merit, so they remain obstinate in the face of the realities of law, and what is recognised within a legal system, frustrating the magistrate and wasting the courts time with unintelligible gibberish. Ultimately, the court is empowered by summary convictions procedure to remove the defendant from the court right there and move onto the next case.

In some situations, the court can even decide the matter in their absence. (ex parte) This is the reason magistrates routinely leave the courtroom in these situations, to avoid wasting court time arguing about frivolous matters. It is not the responsibility of any court to offer legal advice to a defendant. They can try to explain the inconsistencies briefly, but then adjourn matters to another date to give the defendant time to seek adequate legal advice.

Freeman v National Australia Bank Ltd [2006] FCAFC 67:

“vexatious proceeding” includes:

- a proceeding that is an abuse of the process of a court or tribunal;

- a proceeding commenced to harass or annoy, to cause delay or detriment, or for another wrongful purpose;

- a proceeding commenced or pursued without reasonable grounds;

- a proceeding conducted in a way so as to harass or annoy, cause delay or detriment, or achieve another wrongful purpose;

Order 21 rule 2 [Federal Court Rules] provides:

Where any person (in this rule called the vexatious litigant) habitually and persistently and without any reasonable ground institutes a vexatious proceeding against any person (in this rule called the person aggrieved) in the Court, the Court may, on application by the person aggrieved, order that the vexatious litigant shall not, without leave of the Court, institute any proceeding against the person aggrieved in the Court and that any proceeding instituted by the vexatious litigant against the person aggrieved in the Court before the making of the order shall not be continued by him without leave of the Court.”

Section 4 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 defines “proceeding” as:

“a proceeding in a court … and includes an incidental proceeding in the course of, or in connexion with, a proceeding, and also includes an appeal.”

The authorities on Order 21 rule 2 were reviewed by Sackville J in Ramsey v Skyring [1999] FCA 907; (1999) 164 ALR 378. The following propositions can be distilled from his Honour’s judgment:

In determining whether particular proceedings instituted in the Court are in fact vexatious, it may be appropriate to take account of proceedings in other courts where, for example, they have authoritatively resolved the particular issue against the person instituting the proceedings;

- (a) the expression “habitually and persistently” implies more than “frequently”; “habitually” suggests that the institution of a proceeding occurs as a matter of course, or almost automatically, when the appropriate conditions (whatever they may be) exist; “persistently” suggests determination, and continuing in the face of difficulty or opposition, with a degree of stubbornness;

- (b) whether a person “without any reasonable ground institutes a vexatious proceeding” is to be determined objectively, and it is therefore immaterial that the person may believe in the justice of his or her argument and may not understand that the argument has been authoritatively rejected;

- (c) where a final decision has been given, any attempt, whether by way of appeal or application to set it aside, or to set aside proceedings to enforce such decision, which is in substance an attempt to relitigate what has already been decided, is the institution of legal proceedings for the purposes of the rule.

Sackville J based these propositions on existing authority, including Attorney-General v Wentworth (1988) 14 NSWLR 481; Jones v Skyring [1992] HCA 39; (1992) 66 ALJR 810 and Hunters Hill Municipal Council v Pedler [1976] 1 NSWLR 478. The propositions have been approved in later cases in the Court: Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Heinrich [2003] FCA 540; Horvath v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [1999] FCA 504; Granich & Associates v Yap [2004] FCA 1567. In our view they accurately reflect the law on Order 21 rule 2.

Rules of the W.A. Supreme Court 1971 – Order 67 Rule 5 – Procedure in case of Abuse of process:

(1) If any writ, process, motion, application or commission, which is presented for filing, issue or sealing appears to the registrar to be an abuse of the process of the Court or a frivolous or vexatious proceeding, the registrar shall refuse to file or issue such writ, process, motion, application or commission without the leave of a judge or a master first had and obtained by the party seeking to file or issue it.

Nibbs v Devonport City Council [2015] TASSC 34:

“As it was asserted in the appeal outline, the argument amounted to the proposition that where there was a constitutional argument, federal jurisdiction applied, and that the Constitution was the only source of judicial power. Mr Nibbs did not expand on this. I take it that what he meant was that as, on his argument, a constitutional issue arose, s 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) should have been complied with, and notices given to Attorneys-General. However, this was not a cause pending in a State court exercising federal jurisdiction, nor does any matter arise under the Constitution or involving its interpretation.

A matter will not arise under the Constitution if it does not really and substantially, or genuinely, arise: see ACCC v CG Berbatis Holdings [1999] FCA 1151; (1999) 95 FCR 292 at 297; Danielsen v Onesteel Manufacturing Pty Ltd [2009] SASC 56 at [25]–[30]; Pham v Secretary, Department of Employment and Workplace Relations [2007] FCAFC 179 at [12]. A constitutional point must not be trivial or vexatious, or frivolous in the sense of being patently unarguable or completely devoid of merit. It was proper for the magistrate to proceed, and proper for this Court to determine the appeal.”

Shaw v Attorney-General for the State of Victoria [2011] VSCA 63:

“One form of abuse of process is commencing a proceeding which has no prospect of success, that is, is hopeless or, as his Honour said, is ‘foredoomed to fail’. Where a proceeding has no legal merit whatsoever, it would be a waste of the Court’s time to have to deal with it. The reason for that requirement in the Supreme Court Act is obvious enough. A person is declared a vexatious litigant when the Court has been persuaded, on the application of the Attorney-General, that the person has persistently engaged in litigation of a vexatious or hopeless kind.

Beach J concluded, for reasons which his Honour gave, that the proceeding proposed by Mr Shaw was hopeless, that it was without legal merit and was therefore foredoomed to fail. Mr Shaw had failed all together to satisfy him that the proposed proceeding would not be an abuse of process. His Honour came to precisely the opposite conclusion, namely that the proposed proceeding would be an abuse of process and accordingly that he was bound by law to refuse the application.

It is important to point out that the characterisation of the proposed proceeding as ‘an abuse of process’ does not suggest that Mr Shaw is not genuine in his concerns. It is clear enough from the way he presents his argument, both orally and in writing, that he believes passionately in the matters which he argues. Nor does the conclusion imply that Mr Shaw is acting dishonestly or improperly or deceitfully. The question, quite simply, is whether the proposed proceeding has any legal merit. As I have said, this Court has to focus on those matters which do have merit and not spend time on those that do not.

The difficulty (and it is insoluble) is that Mr Shaw and those in court supporting him are very firmly – passionately – of the view that his arguments do have legal merit and, moreover, that this Court should entertain them. That is a problem to which the Supreme Court can provide no solution, as none of the arguments proposed by Mr Shaw has any legal merit at all, and this Court has no jurisdiction to consider the kinds of matters that Mr Shaw wants to ventilate.

This is just the latest in a series of rulings by different judges expressing essentially the same view, that the arguments advanced by Mr Shaw are legally unintelligible. His propositions do not engage any of the principles of law which this Court is bound to apply. Applying those rules, Beach J was entirely correct and I would therefore refuse leave to appeal.

So far as Byrne v Armstrong is concerned, a difficulty for Mr Shaw is that that decision was overruled in Re Shaw & Anor. However, Mr Shaw counters by saying that the Court is “estopped” from relying on this judgment (Re Shaw & Anor). It is not immediately clear on what basis the Court can be “estopped” from relying upon one of its own decisions – let alone a decision of the Court of Appeal in which five judges sat.

If the Constitution Act 1975 (Vic) is invalid, it follows that this is not a validly–constituted court and, if it is not a valid court, then there is no point in Mr Shaw’s being here. That is a fundamental obstacle. The very arguments which Mr Shaw wants to present are arguments which show that the court does not exist, has no valid powers and is comprised of judges who were not validly appointed.

He also said in the course of his submissions something along these lines: “If you’re pooling writs and trading birth certificates, you’re not the Supreme Court, you’re a branch of the stock exchange.” This statement highlights the inescapable internal contradiction in Mr Shaw’s spending time arguing his case before a non-existent court.

Mr Shaw went so far as to say that there was a “secret government”. Mr Shaw says that the agenda of that secret government is the “destruction of each State economy and each State government”. He went on to say: “Something absolutely destructive is happening.”

If there was any truth in these assertions, it would be of great concern to citizens. He should be spending his time alerting other members of the community, rather than two judges who have no power to deal with these matters.”

Glew & Anor v Shire of Greenough [2006] WASCA 260: (at 29)

“…the appellants’ submissions are based on a misunderstanding of the Commonwealth and State Constitutions and are entirely lacking in legal merit.”

Upheld by the High Court in Glew & Anor v Shire of Greenough [2007] HCATrans 520:

“We agree, and the same expression applies to the prolix, offensive and vexatious documents filed in support of this special leave application.”

In Glew v The Governor of Western Australia [2009] WASCA 123 the Court found 42 grounds of appeal were “entirely without merit”, (at 21) “incomprehensible” and “incorrect or irrelevant legal propositions” and a number of them to be “scandalous and offensive” (at 17). The court noted (at 23) that:

“The appellant needs to understand that he cannot simply revisit in other guises issues that have been decided against him. The persistent re-agitation of these issues is a waste of the time and resources of the court and puts the other party to significant expense and inconvenience. It cannot continue.”

Glew v Frank Jasper Pty Ltd [2012] WASCA 93 (at 22):

“The appellant has persisted in running arguments that have already been decided against him, without regard to the inevitable waste of the time and resources of this court and of the party on the other side. No purpose can be served by repeating failed arguments and to continue to do so is an abuse of the system.”

Glew v White [2012] WASC 138 (at 11):

“This appeal is an abuse of process. The appellant is well aware that his idiosyncratic contentions have been repeatedly rejected in other cases. The appellant has invoked the court’s process and procedures for an illegitimate or collateral purpose, namely, as a platform for advancing his nonsensical theories. He appeared at the hearing with the support of a large retinue who appear to share or sympathise with his views. The appellant is not interested in securing justice according to law (either in relation to the convictions in question or otherwise) in accordance with the system of justice administered by the courts of this State. At the hearing on 5 July 2012 he advanced arguments in language which was often disparaging and derisory of this court and the functions it performs.”

Re Glew; ex parte the Hon Michael Mischin MLC, Attorney General (WA) [2014] WASC 107 (from 59):

“This was absurd histrionics. He is not, and was not, a Commonwealth official; there was no basis for charging anyone and his remarks were nothing less than preposterous. The incongruity of Mr Glew’s contentions, and of his claims, was plainly obvious to their Honours and must have been obvious to any fair-minded, reasonable observer. No such observer could attach any credit or plausibility to Mr Glew’s behaviour, which was that of an ignorant man disastrously pursuing his own obsession.”